Step 6: Packing the cargo transport unit

The packer is legally responsible for ensuring the dangerous goods are correctly presented and the cargo transport unit safely packed 43. There are a number of pre-packing checks the packer should build into his procedures to ensure that everything is in order before packing commences.

These checks will identify problems in advance, and add to the safety of the consignment, and assist the cargo handlers who will physically lift and stow the cargo. There are suggested checklists included in the Appendix to this Guide

www.unece.org/trans/wp24/guidelinespackingctus/intro.html

-

43Further guidance can be found in the CTU Code:

Before packing commences, the packages and documentation should be checked by a competent person and the following checks made:

- The transport documents containing the shipper’s declaration(s) contain the full details

- The packages have been checked for marks and labels, especially packages made up into palletised unit loads

- The package marks and labels tally with the details on the transport document

- Confirm that segregation checks for mixed hazard goods have been successfully carried out

- Packages are checked for damage and any damaged packages are set aside

- The packages are assessed for size, weight and strength

- Any requirement for special handling equipment (e.g. drum clamps) is noted

- Any special factors of the packages or stow are noted

- Lashings, strops, air bags, pallets, timber and sheet material to support and brace the stow are available to the packers

With the information about the consignment complete, a competent person should create a stow plan and load list that can be given to the packers 44 and handling equipment operators.

This should guide the packers so that packing takes account of the following key factors:

- The size and type of packages so that weight is distributed evenly throughout the shipping container

- That packages are stacked in a way that does not overstress any individual package

- That adequate securing and bracing of packages is done and gaps can be filled during packing using materials as necessary to ensure the packages do not move in transit

- The stow plan should indicate which packages are heavy and which are light, with the lighter packages stowed on top of the heavier.

- The stow plan should allocate cargo weight distribution (see diagrams below).

Lateral stress placed on cargo during lifting as container tips causes packages to shift resulting in a risk of crushing. Apart from the risk of packages being breached and allowing dangerous goods to escape, the lifting equipment may be damaged, or overbalance, adding physical injury and plant damage to the hazards of not balancing the stow.

-

44 IMO/ILO/UNECE Code of Practice for Packing of Cargo Transport Units (CTU Code), Chapter 3.2, 8, 9.1, 9.2 and 9.3

The cargo transport unit 45 into which the cargo is packed becomes a “package” for the dangerous goods during the sea journey, so it must be checked to ensure that it is suitable for its job. The following section applies specifically to containers, but some aspects will also apply to vehicles loaded to ro-ro ships.

Before packing any cargo transport unit, the condition of the unit should be visually checked by a responsible person to determine the following

- Is it clean, dry and safe for packers to work in? Ensure any marks and/or placards relating to previous shipments are removed.

- Is it suitable for dangerous goods?

- Is the container structurally sound?

- Is it within the legal safety inspection date?

- Is the plated capacity sufficient to carry the weight you intend to pack? Check the maximum cargo weight marked on the right-hand door.

Reject any cargo transport unit that is damaged or unsuitable.

Residue

Residue or contamination on the floor may be a hazardous substance that will injure your employees or react with or spoil your cargo. Reject a contaminated container or clean it, having regard to potential injury to cleaners from an unknown substance.

Pest contamination

The CTU Code states “All persons involved in the movement of CTUs also have a duty to ensure, in accordance with their roles and responsibilities in the supply chain, that the CTU is not infested with plants, plant products, insects or other animals”46.

Structural damage

Check visually for any indication of excessive corrosion, cracks or impact damage to main floor bearers or corner posts that may make the shipping container unsafe to lift.

Floor condition

Check that floor panels have not been damaged by overloaded forklift trucks.

Holes and leaks

Check for holes in the roof and sides – many packages will be susceptible to damage from rain or seawater, and some dangerous goods react violently on contact with water. Subject to safe working procedures, one method to detect holes is to stand inside the container and close the doors.

Nails in the floor

Check the floor for nails protruding from the floor and remove them. Timber blocks and battens are often nailed to floors, and protruding nails are often left behind. These are a frequent cause of damage to pallets and packages, particularly drums packed direct to the container floor.

Old placards

Remove any redundant dangerous goods marks and placards from previous use – check both sides, and both ends – if they cannot be removed, ensure they are painted out.

Container data plate

Check the inspection information on data plate on the door.

Left: ACEP data plate - continuous inspection

Right: data plate with next due inspection date stamp

If the plate displays the letters “ACEP” it means the container operator subscribes to the Approved Continuous Examination Program and the container will meet the Container Safety Convention requirements for five yearly and 30 month examinations, and will normally also be inspected more frequently when the container passes through the operator’s depot. If there is no ACEP mark, the data plate is stamped with the next due date for inspection. If the date has expired, reject the container. However, do not rely only upon data plate date stamps – use visual inspection and common sense.

-

45 IMO/ILO/UNECE Code of Practice for Packing of Cargo Transport Units (CTU Code), Chapters 4 & 8 and Annex 4

46 https://www.iicl.org/iiclforms/assets/File/Pest_Contamination_Cleaning_Guidelines_Feb_2017.pdf

The way the packages of dangerous goods are packed into a shipping container is the most important factor in making the transport safe. Poor packing leading to in-transit package damage, leaks and spills is the most common cause of damage to goods of all kind in cargo transport units. When dangerous goods are involved the potential consequences for ships are amplified. The following guidance is based on observation of numerous incidents. Follow the guidance and it will help you to avoid the most common problems.

Never pack damaged packages into a shipping container

It is an over-riding principle that damaged or leaking packages are not packed into a cargo transport unit. This applies to hazardous and non-hazardous materials. Despite this, it is not uncommon to find that leaking packages have been packed.

Packages are accidently damaged from time to time during the handling as a result of human error, or use of unsuitable handling equipment. Individual cargo handlers may be reluctant to draw attention to the fact that they have caused damage for fear of repercussions, and companies may find it more convenient to conceal damaged packages in a freight container than to set them aside and accept the cost of clean-up, disposal, short-shipment or delays waiting for replacement packages. This is not acceptable.

Spillages of dangerous goods may react with the floor of the container, timber packaging/pallets or other cargo in a dangerous and unpredictable way. Spillages of non-hazardous goods may react with other cargo, spoil or taint other cargo, or damage other packages.

Pack dangerous goods closest to the door

If you are packing a cargo transport unit with a mixture of dangerous goods packages and non-hazardous packages, always put the dangerous goods packages closest to the door, if possible, with the labels also facing the door. In case of spillage or problem with the dangerous goods, it is preferable that they are packed next to the doors where the hazard class can be immediately identified when the emergency responders are able to access the contents of the container.

If the dangerous goods are stowed at the front of the shipping container, and there is a dangerous release from broken packages, the whole container will have to be unpacked by workers in protective equipment before the dangerous goods are reached. This makes emergency response much more difficult, lengthy, expensive and potentially dangerous.

Packages are only required to have labels on one side (two sides for IBCs) so as far as possible, packages should be stacked so that the labels are facing the door, where they can be seen by persons unpacking the shipping container or dealing with a problem.

Packages stacked with dangerous goods labels facing the door

Pack solids over liquids

When drums of liquid have to be packed with packaged solid goods, never pack so that solids are over-packed by liquids. In general liquids are often heavier than solids, so it makes sense to pack with weight down, provided the drums are strong and can bear the weight. However, the main reason is for safety. If the drums leak, there will be a release of liquid that will first be drawn downwards by the force of gravity, and will then spread horizontally along the floor.

If the packages of solid goods are stowed on top of the drums, contact between the solid goods and the spilt liquid will be reduced. This reduces the risk of a dangerous reaction, and it is possible that no damage to the solid goods occurs at all.

If solids are stowed on top of liquids, even if a drum becomes damaged and fails, there is a good chance that packages stowed above will remain unaffected

Over-stowing cargo in shipping containers – Light over heavy

Over-stowing of one sort of cargo by another is proper and normal practice, when done with regard to the strength and weight of packages involved. However, there are many recorded incidents of packages of cargo in shipping containers being crushed because they were over-stowed by goods heavier than they could bear.

To pack a cargo transport unit safely takes skill and planning based on awareness of the strength and contents of the packages.

It may seem obvious that it is not a good idea to pack heavy machinery parts on top of fibreboard boxes containing fragile goods such as aerosols or glass bottles. To an experienced packer, it is a simple decision to pack the heavy cases first, and put the fibreboard boxes on top. However, an unskilled packer may not appreciate the weight difference and simply see an opportunity to build a flat platform of fibreboard boxes that are perfect on which to place the heavy machinery. The fibreboard boxes may survive the packing process but collapse once the cargo transport unit starts moving.

Inexperienced packers may mean no harm, but can do great damage to cargo without intention, simply because they do not understand the forces that will work on the shipping container at sea.

Packages are tested under the UN package certification system for stacking strength by stacking them and leaving them for a period of time in a motionless situation, although vibration test protocols are becoming available.

Stacking tests do not fully replicate the rigorous conditions inside a cargo transport unit in transit, where the packages are subjected to all kinds of motion and vibration. In reality, despite passing a static stacking test, the lower tiers of cargo may collapse under their own weight, as demonstrated in this photograph

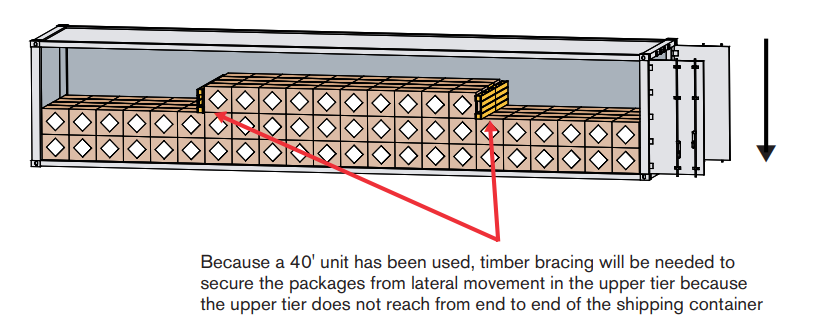

Using sheet material between tiers is always recommended as a way of evenly distributing the weight. A more effective way is to use a 40' container in preference to a 20'.

Goods may physically fit within the cubic capacity of a 20' container, but that does not mean it will travel safely. If the cargo from a 20' container is placed in a 40' container the stack weight on the lower tier of packages will be halved. Although it will cost more to ship a 40' container, it may make the difference between a consignment arriving safely and intact, or damaged and unsaleable.

Stacking strength of packages is difficult to judge, and expensive errors are frequently made. If the shipper has chosen packages of doubtful robustness, the forwarder should make the shipper aware of the safer option of paying a little more for a 40' container.

Some substances, particularly of Classes 4.1, 4.2 and 5.2, are sensitive to heat, or are liable to self-heat. Consignments of packages may need to be packed for transport such that air can circulate between individual packages. This helps to dissipate heat from local areas and prevent “hot spots” from developing deep inside the container. Reefer containers may be specified by the shipper to provide thermal control.

Shippers must provide clear guidance on packing if this system is required. Packages may be stacked directly into the container or may be palletised. Gaps left between the packages should not be so large as to create “point loading” effect on the corners of the packages.

It may be desirable to use a 40' container in preference to a 20' to keep the stacks as low as practicable. This will enable the stack heights to be halved and the air space inside the shipping container to be maximised.

While clearly air circulation is an important consideration, it is critical that appropriate account is taken of the need to block, brace and secure cargo to protect it against the dynamic forces that will occur during transport.

Steel and plastic drums of around 200 litre capacity are a common package choice for dangerous goods, but drums of up to 400 litres are acceptable for some products. A 20' container will comfortably take 80 x 200 litre steel or plastic drums and this is a common consignment. Drums are produced in a range of smaller sizes.

Strength and resistance of drums

Drums can be very robust, particularly plastic drums and steel drums with plastic liners, but both are vulnerable in certain areas. If drums that contain liquid are punctured, there is the obvious potential for a significant release of dangerous goods from a small hole.

Plastic and steel drums will withstand a fair amount of rough handling before the sidewalls rupture, and will deform extensively on impact before rupturing. Plastic drums will retain their original shape after a severe impact, but they are prone to blowing out their closures if subjected to sudden impact such as dropping. Also at very high temperatures and in strong direct sunlight the walls soften, giving them less resistance to cutting and a greater liability to lose rigidity if over-stowed heavily. Both materials are vulnerable to cutting if the sidewalls are struck with a sharp object.

If heavily over-stowed, plastic drums are liable to deform gradually, making the whole load unstable. Steel drums largely avoid this.

High quality modern drums are resistant to damage, but are not indestructible

Handling drums on pallets

It is common to pack drums to a pallet as several can be handled in one lift, and no special drum-handling equipment is needed. However, forklift drivers need to be aware that steel drums puncture easily – they need to take care when working that the forklift arms do not protrude beyond the pallet being lifted, and stab the nearside drum on the pallet previously positioned. This is a common type of incident during packing, because it occurs outside the operator’s range of vision.

Punctured drums MUST be removed from the cargo transport unit

Drums leaking from damage received during packing are sometimes not removed from the container, causing problems later in the journey. If dangerous goods are involved, emergency procedures should be instigated by the forklift operator.

Drums stabbed by forklift - a common cause of drum damage during handling

Recommended good practice for handling drums:

- Drums are easy to handle if the right handling equipment is provided.

- Loose drums are best handled using appropriate drum clamps attached to forklifts.

- Drums banded to pallets can be lifted four or more at a time, and can be packed using a conventional forklift.

- Palletised drums should be banded or film-wrapped tightly together, and banded to the pallet.

- Excessive manual rolling of full steel drums should be avoided, particularly over rough concrete, muddy ground, or ground containing small stones, as the drum seams or sidewalls can be damaged and stones can get embedded on the bottom of drums, and can cause punctures to the drums later in transport or during handling.

Drums on pallets should be wrapped with film or banded to keep them bound together as a unit

Drums being packed with drum clamps

Banding on pallets

Steel drums are also prone to sideways chafing if the rolling hoops align exactly during extended transit, particularly by rail, which can generate intense vibration.

Rolling hoop chafing

Drums can be worn away in transit where the rolling hoops line up and are in contact for extended journeys.

Recommended good practice for avoiding sideways chafing

In order to avoid edge to edge contact of the rolling hoops, particularly for long sea journeys, it is advisable to put plastic or heavy cardboard sections between drums bound together on pallets to prevent metal-to-metal abrasion.

Drums on the roll47

It is forbidden to stow drums containing dangerous goods “on the roll”. Drums have closures at the top that are not designed to be below the liquid level.

Drums containing dangerous goods shall always be stowed in an upright position unless otherwise authorised by the competent authority

Using sheet timber spreader sheets between tiers of drums

Steel drums are designed to be stacked in tiers, and are often loose-packed into cargo transport units using drum clamp attachments.

However, steel on steel contact between the upper and lower drums during a sea voyage provides no resistance to movement, and the drums are liable to slide, causing the metal of the upper drum to be worn away on the lower rim seal, and drums to abrade against the container walls. This can lead to leakage from drums in the upper tier.

Placing sheet timber material between the layers of drums can easily prevent this sliding motion and reduces the build-up of pressure points motion where drums abrade against each other. Low-grade plywood is suitable, but chipboard is not recommended as it has less integral strength and degrades quickly in damp conditions.

Placing timber sheet between tiers of plastic drums also makes the stow more rigid and stable.

-

47 IMDG Code, 2022 Edition Amendment 41-22, Section 7.3.3.4

Stacking and wrapping packages to pallets to make unit loads is universal practice. However, some problems can arise from careless use of pallets, and pallets can be the indirect cause of serious releases of dangerous goods.

Point-loading – pressure damage to cargo overstowed by palletised goods

Palletised cargo stowed in upper and lower tiers inside cargo transport units can damage the cargo below, if the packages below are susceptible to pressure damage. This occurs if the weight of the palletised cargo is transferred to the goods below through the pallet’s corner blocks, and is not spread evenly. The result is point-loading.

Point loading

Here, a pallet has damaged the drums below. The indent of the pallet above can be seen on the top of the drum in the corner. This could have been prevented by using a spreader sheet of plywood between the tiers of pallets

If the packaging of the goods on the lower tier is susceptible to point-loading damage, for example bags, plastic drums, paint pails, plastic and light steel jerricans (particularly the commonplace 5 litre light steel jerricans frequently used to retail dangerous goods), the packaging can collapse. This allows the product to escape and the pallet to further collapse.

If the surface of the cargo onto which the upper tier of pallets is packed is uneven, for instance bagged cargo, rounded plastic drums, or if the sizes of the packages on the lower tier is uneven, the pallet above may deform to the point of partial disintegration, causing further potential damage to cargo from protruding nails or split wood. The upper tier will become unstable if pallets break up, causing the cargo to shift inside the container, causing further cargo damage and further load instability.

Recommended good practice to avoid point-loading

The best protection is the provision of a layer of timber sheet material placed over cargo on lower tiers to spread the weight of over-stowed pallets evenly and prevent point loading. Low-grade plywood sheeting commonly used in the construction industry (shuttering board) to retain liquid concrete is suitable as it is robust, economical and widely available.

Common problems caused by pallet failure

Some pallets are robust and have strong lower bearers and flat load bearing upper panels made of solid boards. Heavyweight pallets are made for repeated use, are resistant to deformation, and can bear substantial loading without deformation or risk of disintegration. However, many pallets are designed for single use, and are constructed simply, economically and use low quality timber. Many are of extremely light and flimsy construction. This is acceptable provided the limits of the pallet are taken into account. Heavy cargo placed on to light grade pallets will deform or break the bearers.

The less robustly the pallet is constructed the more likely the pallet bearers will deform both under the weight of the cargo, and to the shape of the surface beneath. Even if the cargo is not damaged in transit, deformed pallets can make unpacking the goods by forklift very difficult, particularly when stowed with flexible IBCs. When pallets break up, it is often difficult to remove cargo from cargo transport units without causing further damage to the packages of cargo.

Lightweight pallets have been used for heavy cargo that has caused the pallet to break up and point packing has caused the plastic drums beneath to deform and collapse

It is common for a forklift operator to accidentally stab a package with the forks underneath the pallet while attempting to pack or unpack collapsed pallets. Flexible IBCs (usually 1-tonne woven polyester bags) damaged in this manner may release considerable amount of product and are difficult to handle manually. If fine powders such as carbon black are released, the recovery operation is dirty and contamination is difficult to contain.

If palletised boxes or 25 kg bags are involved, the pallet loads can be broken down manually and unit loads dismantled piece by piece. This adds greatly to the time and cost of handling, and defeats the objective of unitising the cargo in the first place. It also adds to the risk of individual packages being damaged during manual handling, and the time and cost of unpacking a container of dangerous goods in this way is considerable if workers need to wear breathing apparatus and protective clothing.

Recommended good practice to avoid collapse of pallets

It is best to select pallets strong enough to accept the mass to be borne by them. It may sound obvious but it is surprising how many times pallets are simply not strong enough to perform their function – to support the mass of the cargo during mechanical handling. It is accepted that in many situations there will not be a great choice of pallets, and perhaps only lightweight economy pallets are available.

However, such pallets can easily be strengthened by cutting timber sheet material (such as plywood) to the same size as the pallet, and placing it on top of the pallet before packing it, and between tiers if the pallets are being stacked one on the other. This will distribute the weight evenly and help to keep flimsy pallets intact by preventing the bearers from deforming.

Typical nail-puncture damage

Red dye can be seen leaking from a hole made by a nail that was protruding from a broken pallet

Pallet inspection and selection

Many pallets are cheaply made from poor quality timber, and even well-made pallets will break up eventually if continuously re-used. It is common for nails to work out of the top boards and protrude upwards, presenting a risk of tearing bags or puncturing drums placed on the pallets. Such nails are not easy to see, so if old pallets are being re-used, the pallets should be checked carefully for split corner blocks and protruding nails.

Drums in particular present a problem. If placed on top of a protruding nail it is common for the bottom of the drum to be pierced, then temporarily sealed by the nail, so that the packers cannot observe the damage. The hole remains sealed until the container is moved. The nail hole is then gradually enlarged by the nail acting as a file, wearing away the metal or plastic of the drum until the hole is enlarged enough to release the product.

Use of second-hand or economy pallets can appear to be a money saver, but the ultimate cost in cargo damage, extra handling, spillage response costs and incidents caused by release of dangerous goods means that cheap pallets can be a false economy.

Recommended good practice in choice and selection of pallets for dangerous goods

Before using any pallets, but particularly new economy pallets and second use pallets, they should be inspected for protruding nails and rejected or repaired. The use of timber sheeting cut to the size of the pallets will prevent nails from damaging the cargo, while adding to the strength of the pallet. However, low quality pallets are not recommended for use with dangerous goods

Solid frame IBCs are very common re-usable packages, a kind of small tank for liquids or powders designed for convenient mechanical handling. The most common size is around 1,000 litres in capacity and weighing around 1 tonne filled, but they may be up to 3,000 litres. A common design type is a semi-rigid plastic inner receptacle protected by a metal frame with a filler cap on the top and valve near the bottom, filled and discharged by gravity. While the frame is generally sturdy, the inner is vulnerable and not designed to withstand external pressure, point-loading or impact.

Left: Typical composite IBC (Intermediate Bulk Container) - inner plastic receptable inside a rigid metal cage - not designed to be separated in use

Right: An IBC with the top of the inner receptable broken by careless overstowing

Stacking composite IBCs

Most composite IBCs are designed to be stacked, one on top of the other. If they are of the same design, this works well and they nest together securely. However, there is no standard design or size. Many instances have been investigated where IBCs of different shapes and profiles carrying liquids have been stacked two-high in containers, causing a variety of failures of the inner receptacles of the lower tier.

IBCs have data plates that record inspection dates and display symbols indicating the maximum stacking load,48 as shown in the figures below:

Left: Symbol for the IBCs capable of being stacked, with the maximum stack weight indicated

Right: Symbol for the IBCs NOT capable of being stacked

Common causes of IBC failures in transport

The following problems can occur if stacked IBCs do not fit together or “nest” securely one on top of the other, or are carelessly over-stowed with other cargo:

Point loading punctures

If the upper IBC is slightly smaller than the lower, or is misaligned, one or more of the feet of the upper IBC can rest on the inner receptacle of the lower, eventually causing a puncture under pressure, forcing the contents of the lower IBC to be expelled. This leads to tilting of the upper IBC, causing further instability in the load.

Excessive downward pressure on an inner receptacle causes the closure to fail

If the upper IBC is smaller all round than the lower, it can sit inside the frame of the lower IBC, resting on the top of the inner receptacle. This will put excessive downward pressure upon the inner receptacle causing it to deform inwards, which can force the contents past the closure, or cause the closure to rupture, or cause the inner receptacle to fail catastrophically.

Damage during packing

If IBCs do not fit squarely together when stacked in the cargo transport unit because they are not the same size or shape, it is often difficult to use the forklift truck without causing damage to one or other of the units during packing and unpacking. Damage may be done to valves or the vulnerable inner receptacle, out of the line of vision of the forklift driver, perhaps without his knowledge.

Damage from overstowing

When one tier of IBCs is stacked inside a container it is tempting to use the flat tops of the IBCs as a load platform for other goods. IBCs are not designed to accept random overstowing. Unless the overstowed packages are very light in weight, it is easy to apply excessive downward pressure on the IBC, crushing the inner receptacle, again forcing product past the closure, causing rupture of the closure or catastrophic failure of the inner tank.

The inner plastic receptable of this IBC has partly collapsed under the weight of a pallet that gas broken through the top section of the IBC's protective metal frame

Good practice in the packing of IBCs

For the best results, IBCs of different design should not be mixed. If this cannot be avoided, the best solution is to board out on top of the lower tier of IBCs with wooden sheet material, cut to make a false floor. With this in place, the lower tier is protected and a tier of different shaped IBCs can safely be packed on top. With timber sheet material on top strengthened by timber planks or bearers, point loading is avoided, and a single tier of IBCs can safely withstand the weight of items placed on top of them as indicated by the stack weight symbol on the data plate.

-

48 IMDG Code, 2022 Edition Amendment 41-22, Section 6.5.2.2.2

Unsecured packages are a major cause of damage to cargo49. When non-hazardous cargo is damaged, the effect is expensive, time consuming, causes irritation to customers, and can cause cancellation of trade contracts. When the damage involves dangerous goods, it is all these things, plus it can create the conditions for a fire or explosion, catastrophic to a ship at sea, risking death and injury, and widespread cargo destruction, and disruption of the supply chain.

This cargo was insufficiently secured. Gaps were left into which cargo fell and as a result cargo was lost through breakage and contamination

Gap filling using pallets

The aim of securing cargo is to ensure it does not move within the shipping container. Movement results in damage to packages and consequent loss of cargo containment. In an ideal situation, cargo would fit neatly into containers with no gaps between packages of cargo, and no gaps between packages of cargo and the walls of the container. If there are gaps, the gaps must be filled.

Using pallets and timber to fill a gap and make gate between the cargo and the doors

Various methods can be used. A crude but effective method is to use pallets to fill gaps. They are freely available in most packing facilities, are light and easy to fit into place, and a convenient shape. Any smaller gaps between pallets can be filled out with planks of wood.

Pallets can be used in combination with heavy timber struts to produce effective walls to brace cargo. This is not an approved method, but it is a very common procedure, and if done carefully is effective.

Gap filling using air bags

A more sophisticated method of gap filling is to use inflatable airbags. These are more expensive and need air pumps to inflate the bags, but they are very effective. Care must be taken not to over-inflate bags in cold temperatures if the cargo is going to the tropics – as the air inside the bags will expand and could burst the bags.

Using inflatable air bags to fill a gap between rows of pallets

Blocking and bracing

Often there is a large gap between the cargo and the container doors, and it is more practical to build a “gate” behind the cargo, and support that with timber bearers than it is to physically fill the gap.

Timber "gate" to restrain cargo and bracing struts running back from gate to rear corner posts to support the gate restrains both upper and lower tiers of cargo.

Blocking and bracing to achieve equal weight distribution

If individual packages of cargo are heavy, it is sometimes necessary to place cargo in the centre of the container to achieve reasonable weight distribution. This may require blocking and bracing at both ends of the top tier of cargo.

Blocking to prevent fore and aft movement of packages in the upper tier that does not reach from end to end of the shipping container

-

49 IMO/ILO/UNECE Code of Practice for Packing of Cargo Transport Units (CTU Code), Chapter 9.4 and Annex 7

Most cargo transport units are manufactured with lashing points or tie down points along the bottom and top rails. Such anchor points that are provided along the bottom rail are usually rated at 10 kN50 in any direction. The Lashing points along the top side rails are usually rated at 5 kN. There is often also a tie bar running along the side walls at a height of about 1 metre above floor level. These are not designed to take substantial weights. There is no reason not to use lashing points where the cargo allows access, but blocking and bracing and gap filling is often a more effective method of securing cargo.

It is recognised that using strops and ropes to lash down cargo inside cargo transport units using the lashing points provided is difficult – much more difficult than lashing flat racks for instance, where good all-round access is available. Access inside the shipping container after and during packing cargo is usually awkward and restrictive, and it is often not easy to position the lashings where they would be most effective. It is therefore easier and more effective to fill the gaps between pieces of cargo inside box containers to prevent them from moving than to lash them using the lashing points.

-

50 A kilonewton, being the measurement of the force required to accelerate a mass of one kilogram at a rate of one meter per second squared.

When dangerous goods have been packed into a cargo transport unit for sea, a packing certificate must be prepared and signed by the person responsible for packing the container, often the packer. This is often referred to as the ‘Packing Certificate’.51

This is a binding declaration signed by the packer to state that he has checked that the goods have been packed, segregated, marked, labelled and secured in the cargo transport unit in compliance with the provisions IMDG Code, and that cargo transport unit itself is fit to carry the goods.

-

51 IMDG Code, 2020 Edition Amendment 40-20, Section 5.4.2

When dangerous goods have been packed into a shipping container, placards and marks must be fixed to the outside of the shipping container to indicate the hazard class or classes, including sub-hazards of the dangerous goods inside.

Placards must be fixed to both sides, front and back of the shipping container.

Note: The packer is responsible for attaching placards to the outside of the container.

When it is required to display the UN Number, it can be displayed on separate orange panels (right) or on white panels on the placards (left).

Marine pollutant mark55

Marine pollutant marks must be displayed on both sides front and back of a shipping container that contains any dangerous goods classed as marine pollutant.

The marine pollutant mark is added to cargo transport units carrying substances that are environmentally hazardous but not otherwise dangerous, and also to substances that are classified as being both dangerous goods and also environmentally hazardous as a sub-hazard

Limited Quantities mark56

Limited quantity marks must be displayed on both sides and front and back of a shipping container that contains dangerous goods in limited quantities only.

A CTU containing BOTH dangerous goods packed in “limited quantities” and other dangerous goods must be placarded and marked according to the provisions applicable to the other dangerous goods. No “limited quantities” mark is required on the CTU in this instance.

-

52 IMDG Code, 2022 Edition Amendment 41-22, Chapter 5.3

53 IMDG Code, 2022 Edition Amendment 41-22, Section 5.3.1.1

54 IMDG Code, 2022 Edition Amendment 41-22, Section 5.3.2.1

55 IMDG Code, 2022 Edition Amendment 41-22, Section 5.3.2.3

56 IMDG Code, 2022 Edition Amendment 41-22, Section 5.3.2.4